In Turkey, your rights are defended as long as you have friends (and you’re famous)

Turkey’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) government, led by iron-hand President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, has a horrendous record of imprisoning, censoring and harassing journalists. Notably, after the 2013 Gezi resistance movement and Erdoğan’s feud with former ally, religious leader Fethullah Gülen in 2014; the number of legally and economically persecuted journalists skyrocketed. Socialist, Kurdish and recently Gülenist journalists are being either imprisoned, or sacked due to government pressure on media bosses. Vildan Atmaca and Beritan Canözer of Kurdish news agency JİNHA, Erdem Gül and Can Dündar of critical mainstream newspaper Cumhuriyet; Hidayet Karaca and Mehmet Baransu, well-known Gülenist journalists are the latest entries to the appalling record book of Turkey’s systematic journalist imprisonment. Journalism organizations such as Journalists’ Union of Turkey (TGS), Solidarity Platform with Detained Journalists (TGDP) and Pressout continuously demand journalists’ release, with the help of social media users.

However, does every journalist have the same amount of support for their basic rights? Or, does it rather operate based on how famous you are, how mainstream you are or how many influential friends you have? This is a point of discussion in Turkey.

Previously, I used social network analysis to investigate the Twitter users’ interest in the civil war going on in Kurdish regions of the country. This time, I will use once again great social network analysis tools NodeXL and Gephi to question an important debate in Turkey. What I want to do is to compare the cause of six aforementioned imprisoned journalists’ presence on Twitter, hoping to find and show whether they get equal support and if not who supports whom. Once more, I would like to remind that, whereas I mainly use these methods in my academic works, this research does not contain academic validity even though it uses valid algorithms to create network graphs. For a scholarly valid research, these data should be reiterated and validated within an acceptable time period.

First of all, I collected the Twitter messages for six aforementioned imprisoned journalists, between 18–25 December 2015, via NodeXL. I used the query string [“Name Surname” OR #NameSurname] for each journalist, to find the tweets their names are used either as is or as hashtags. Then I exported this data to Gephi, where I applied Modularity Class and Eigenvector Centrality data treatment algorithms to find different clusters within the network and define the most influential nodes (actors) and I visualised them using Force Atlas2. The Pajek (.net) files of each journalists are downloadable from here, for consultation in Pajek, Gephi or simply a word processor.

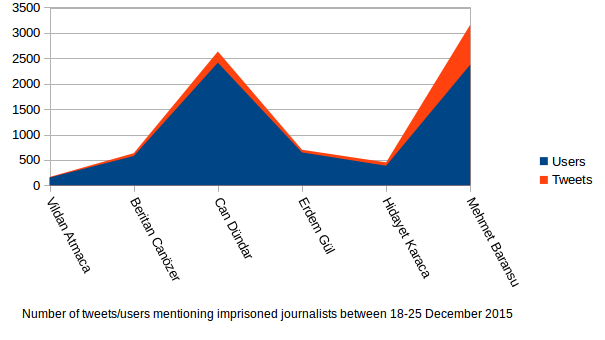

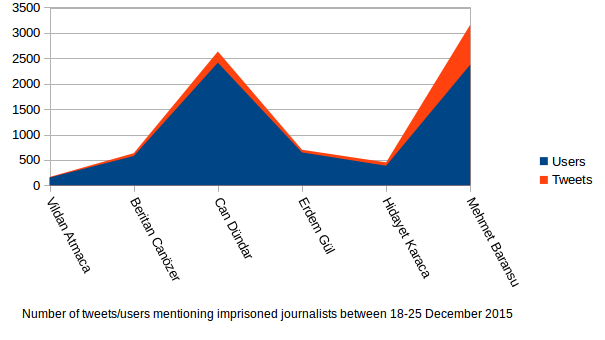

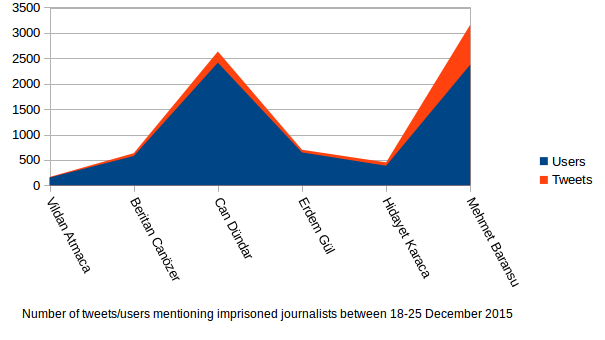

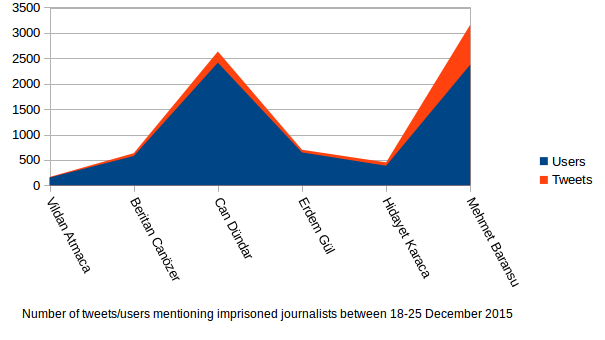

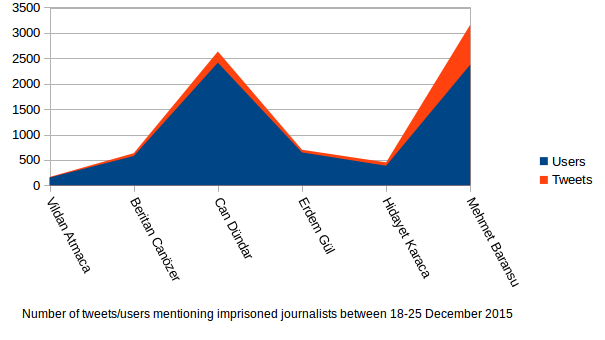

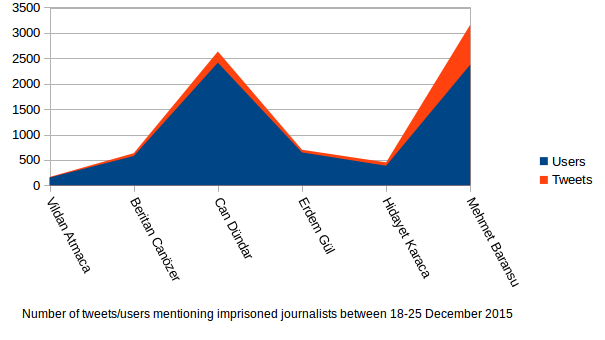

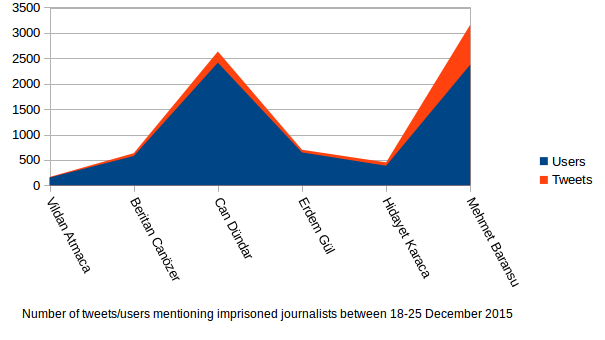

The number of tweets and users mentioning these imprisoned journalist appeared to be a signal of some very uneven findings.

Mehmet Baransu of Taraf newspaper and Can Dündar of Cumhuriyet newspaper are incomparably more famous than the other journalists as they have their own columns in mainstream newspapers and appear on TV regularly. Therefore, maybe it would be unfair to compare these journalists with some quantitative data. So, network graph might be of help to see if fellow journalists and journalism organisations expressed their support to all these journalists equally.

JİNHA reporters Vildan Atmaca and Beritan Canözer received considerably lower number of tweets comparing to their fellow colleagues in mainstream. The users supporting them are also quite concentrated. Atmaca has mainly been mentioned by her own agency, the women’s branch of socialist collective Halkevleri, independent journalism enterprises 140journos and dokuz8haber, fellow female journalist Sibel Yükler and Mehveş Evin. Canözer, whose detainment is more recent, was mentioned by her agency, socialist Evrensel newspaper, Cumhuriyet columnists Ceyda Karan and Murat Sabuncu, and a network of women’s rights and Kurdish associations. One interesting actor in this network is Hasan Cücük, from Gülenist Zaman newspaper.

Cumhuriyet journalists Can Dündar and Erdem Gül also have very differing graphs concerning both quantity and characteristics. Can Dündar’s clusters are led by his newspaper, Mustafa Balbay the former lead writer of Cumhuriyet and current MP, İsmail Küçükkaya from mainstram FOX TV, writer Yılmaz Odabaşı and İhsan Yılmaz from Gülenist Meydan newspaper. Furthermore, one cluster is formed around an anonymous account tatarbaskan which is exclusive to Can Dündar’s network.

Erdem Gül’s network also feature Cumhuriyet and Mustafa Balbay, as well as independent media websites yenitaraf and postmedya. During his incarceration, his own Twitter remains active, posting updates about his legal proceedings, and appears in his network graph. Most of the other names mentioning Can Dündar, do not appear visibly in this network.

Gülenist journalists Mehmet Baransu and Hidayet Karaca also have graph differing from each other. One reason for that is Karaca’s detainment has reached a full year and Baransu being arrested is a rather recent development. But also Baransu is a very visible character of media in Turkey. As a matter of fact, before the Gülen-Erdoğan feud, he was one of the journalists to publish confidential documents criminalizing high-ranking members of the Armed Forces and other people considered to be threats for the AKP government. In Baransu’s graph, almost all Gülenist media outlets and Twitter users appear, such as Zaman and Meydan newspapers, journalist Tuncay Opçin, Gülenist Twitter account caytiryakisi. Meanwhile, Karaca’s network is led by Gülenist news website Aktif Haber and former Today’s Zaman editor-in-chief Bülent Keneş.

One conclusion that may be reached from these graphs is the clusters are mainly led by people and organisations politically close to these journalists and exceptions to this rule are quite scarce. Also, journalists’ organizations and political parties appear in none of these graphs as influential actors, which is intriguing.

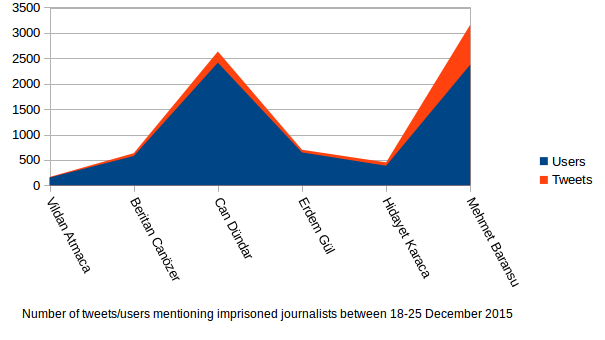

These graphs also pique my curiosity about one other question. The leading actors in each graph, are they interested in other journalists’ cases? Therefore, I picked five most influential users from each graph according to their Eigenvector centrality numbers and checked if they tweet about other cases. The results are as below;

As it may be understood from the graph, Kurdish journalists Canözer and Atmaca were mentioned not by even one of the most influential twitter users supporting mainstream or Gülenist imprisoned journalists. Can Dündar was mentioned much more than Erdem Gül, in all groups’ of users. Generally mainstream journalists were mentioned by the majority of Kurdish and Gülenist journalists’ supporters. Meanwhile, the majority of Kurdish and mainstream journalists’ supporters did not mention Gülenist journalist, however it should be noted that Baransu and Karaca’s cases date further back comparing to the others’ which might affect people’s attention in their cases, bearing in mind Turkey’s strikingly fast pace of changing agenda.

This graph more or less shows that every journalist is majoritarily supported by their own entourage, and it is way more likely to get attention if you are famous and/or work in mainstream media. This situation may be considered to be normal. However, sadly in Turkey, the relationships among journalists and their institutions are also shaped by this popularity contest. Last Saturday, journalist organizations arranged a rally in Istanbul, to demand imprisoned journalists’ release. This rally was dubbed “30-step march,” a reference to 30th day of imprisonment for Can Dündar and Erdem Gül. While the spokesperson of the rally, Ceyda Karan (who also appears in our research as a user who supported Kurdish journalists) underlined that they “demand(ed) that not only Dündar and Gül but all jailed journalists be released,” the rally from the beginning to the end seemed to be a protest against Dündar’s (and maybe Gül’s) imprisonment exclusively. Before the rally, the press bulletin distributed by the group featured only Dündar’s and Gül’s name. The other recently imprisoned journalists’ names were not mentioned, meanwhile, intriguingly the Oda TV (an ultra-nationalist independent news website of which the editor-in-chief, Soner Yalçın, was incarcerated between 2011–2012) case appeared in the press bulletin. In order to understand this bizarre discrimination, one should know about how journalism functions in Turkey. Notably in Istanbul, where a vast majority of mainstream and independent media is located, the journalists’ professional solidarity depends on personal relationships, rather than institutional ones. Journalism associations and trade unions are very weak, and they also operate on these interpersonal networks, which are heavily constructed around non-professional activities. A Kurdish journalist working in a small news agency or newspaper in Turkish Kurdistan, does not belong to these networks. Not every Istanbul journalist belongs there anyway, after all it is just a large-scale group of friends. (Gülenists also do not belong for a different and more understandable reason, as they have a long history of siding with the police and the government against dissident journalists.) And at the end of the day, when you are harassed by the regime or your boss/editor-in-chief, the support you get may depend on how cosy you were with these networks. For instance, Soner Yalçın’s case of 2011 may seem more memorable to your fellow journalists than your detainment of last week. You may challenge a dreadful regime or your auto-censorship-happy boss, but the peer pressure of your co-workers may get the best of you.